NorthSec 2018

About a month ago I went NothSec, Canada’s premier cyber security conference & CTF. I was lucky enough to go with the SomRandomName team. Unfortunately we didn’t place in th CTF this year but I still learned so much! In this post I’ll talk about some of the challenges I helped solve.

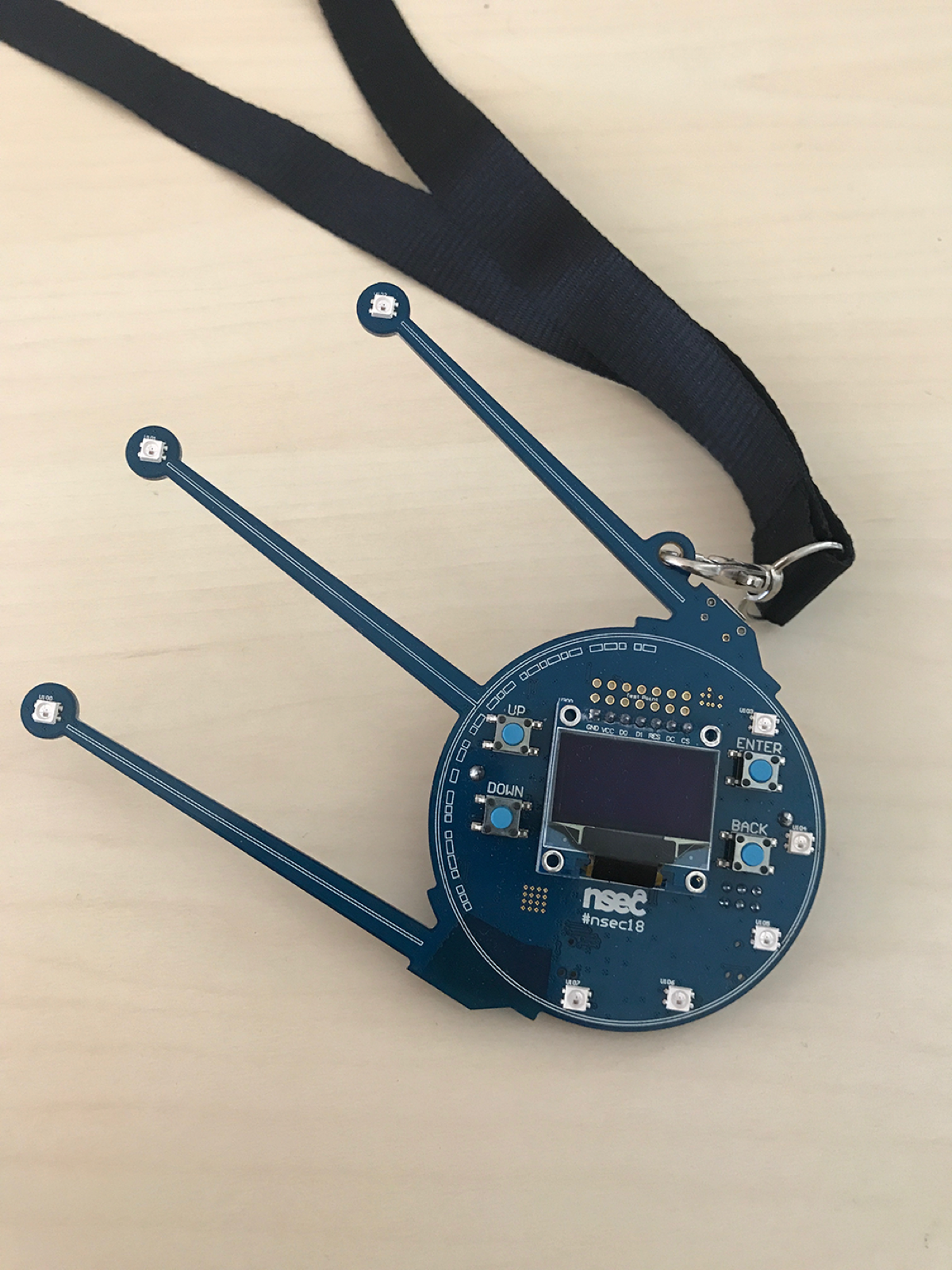

Badge Work

Before I get too much into the challenge its self I want to talk a bit about the badge. At NSec we’re given a PCB with a few features (Bluetooth, LEDs, small display, debug ports, etc…) as our conference badge. During the days of the conference you’re able to analyze the conference firmware, creating tools to interact with the badge. My primary focus of the badge was being able to interact with the implemented bluetoth protocol. We were given some specs regarding the bluetooth so I opted to create a python script which uses the bluetooth controller on my macbook to interface with the badge.

Before diving too deep into the bluetooth operations it should be noted that any modification via bluetooth required the device to be unlocked via a sync key. The sync key could be found within the menus of the badge however one of my teammates noticed that the sync key was actually just derived from 4 bytes in the device name being XORed with 0xc3c3. Once this was determined it became possible to “hack” anyone’s badge. I made this fun little script to perform almost any bluetooth action, though the LED stuff didn’t seem to work fully.

BabyRE 0

We were given this unknown binary, can you find the flag?

- [ BabyRE0 ]

What command might reveal some of the text contents of the binary?

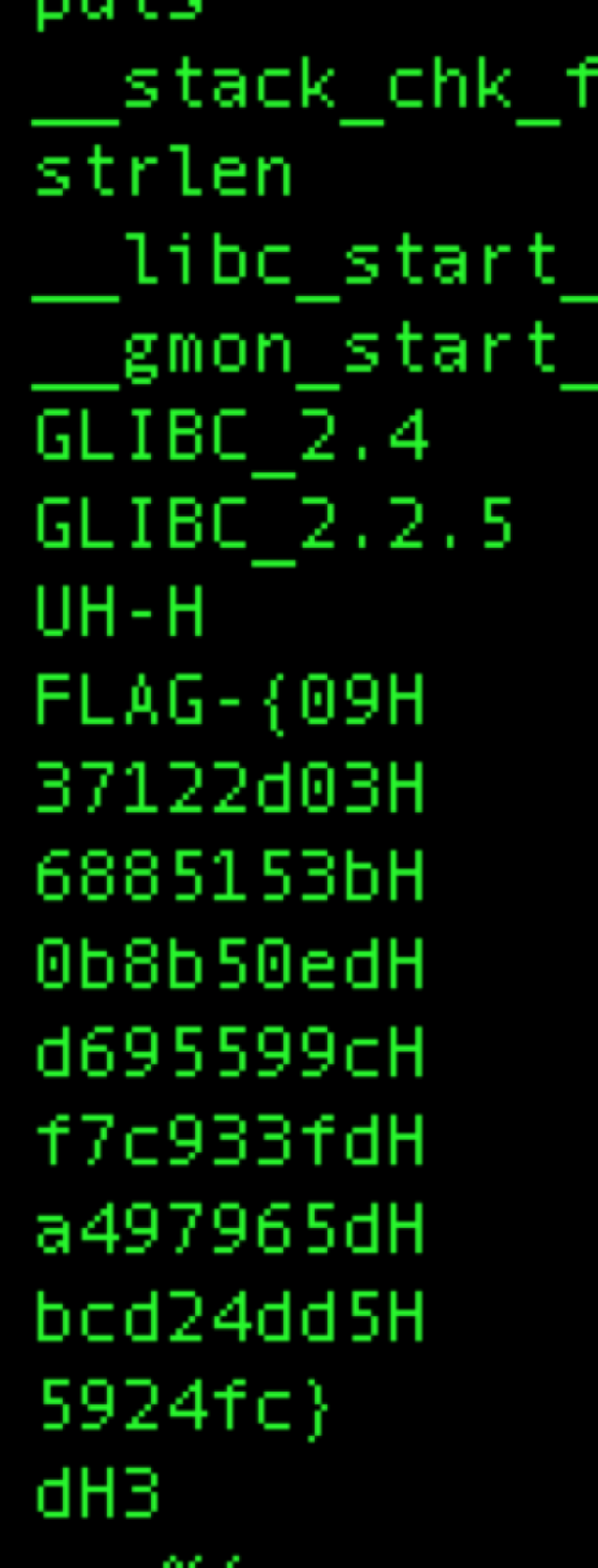

This challenge was pretty straightforward, even as a beginner (hence the title BabyRE). It was the perfect introduction to reverse engineering for me as I haven’t done much in the past. My first instinct was to attempt running strings on the program… and what do you know, it revealed some interesting information!

Based on this information it looks like we have the flag! So I attempted to concatenate all of the lines that appear related to the flag and submit…. nope wrong flag! Looking a bit closer at the flag we can see that the text appears to be only lowercase characters and numbers, infact it looks like hex. Each of the lines end in “H” so perhaps that’s just denoting that the contents are hex? Removing the H reveals FLAG-{0937122d036885153b0b8b50edd695599cf7c933fda497965dbcd24dd55924fc} - submit and bam we’ve got the flag!

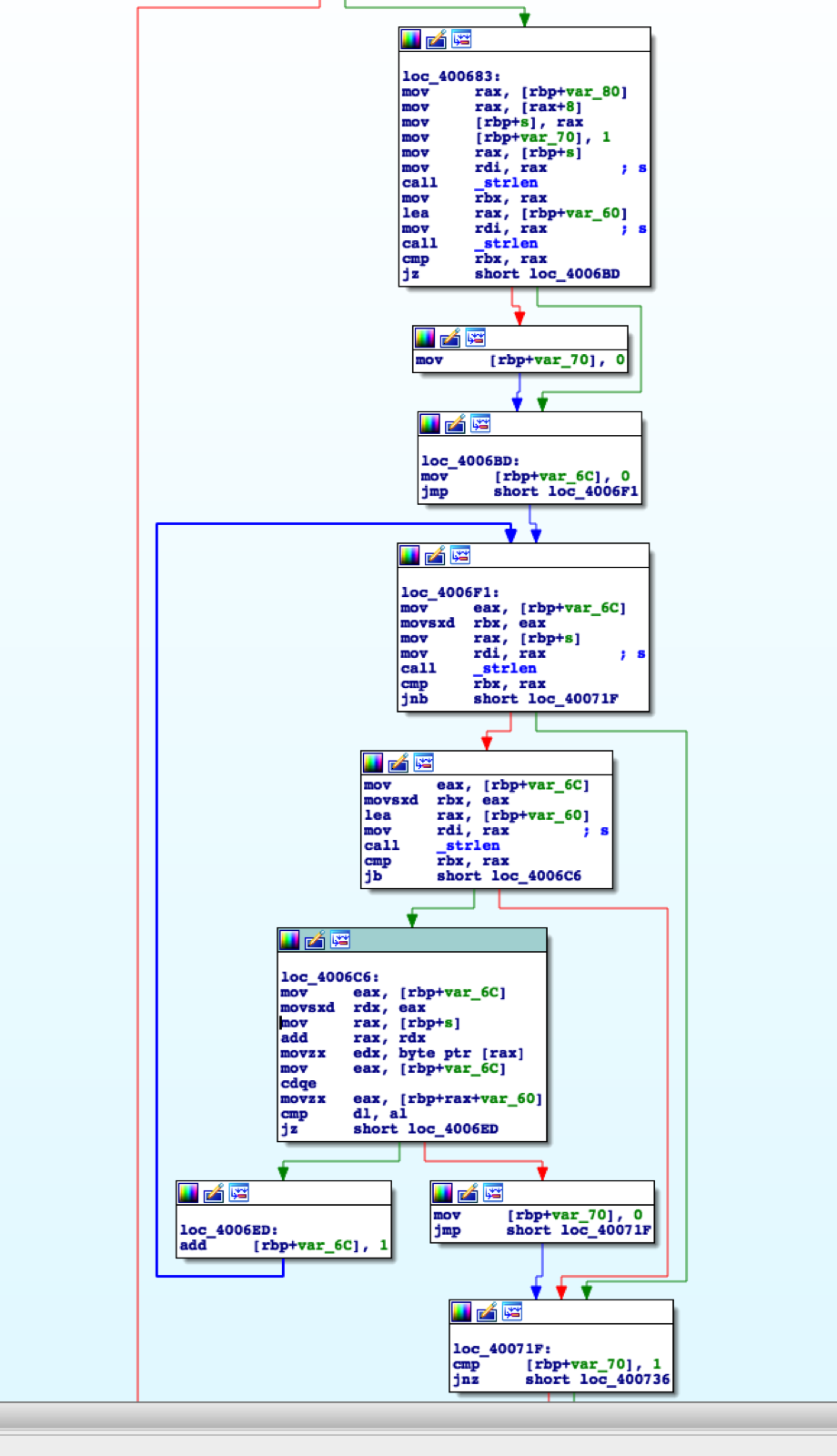

However I didn’t stop there but rather I decided to take a few minutes to look at the challenge in a disassembler (I chose to use IDA) just incase it gave some kind of indication how the upcoming challenges might have operated. For all of the BabyRE challenges I only followed the branches which lead to success, for example if no input fails then I would stop analyzing that branch. I personally found this the quickest way to solve the problems. I’m not going to go into too much detail about the IDA process here since I talk about it more in the BabyRE1 solution, however this is what the disassembly graph looked like:

BabyRE 1

We were given this unknown binary, can you find the flag?

- [ BabyRE1 ]

Does ^ help at all?

Once again I started by running Strings. This time it looks like the string was obfuscated somehow – looks like more work is required. After some basic analysis I decided to hop right into reversing the binary with IDA. In hindsight I probably would have been better off running it through a debugger first with some test input just to see what’s happening.

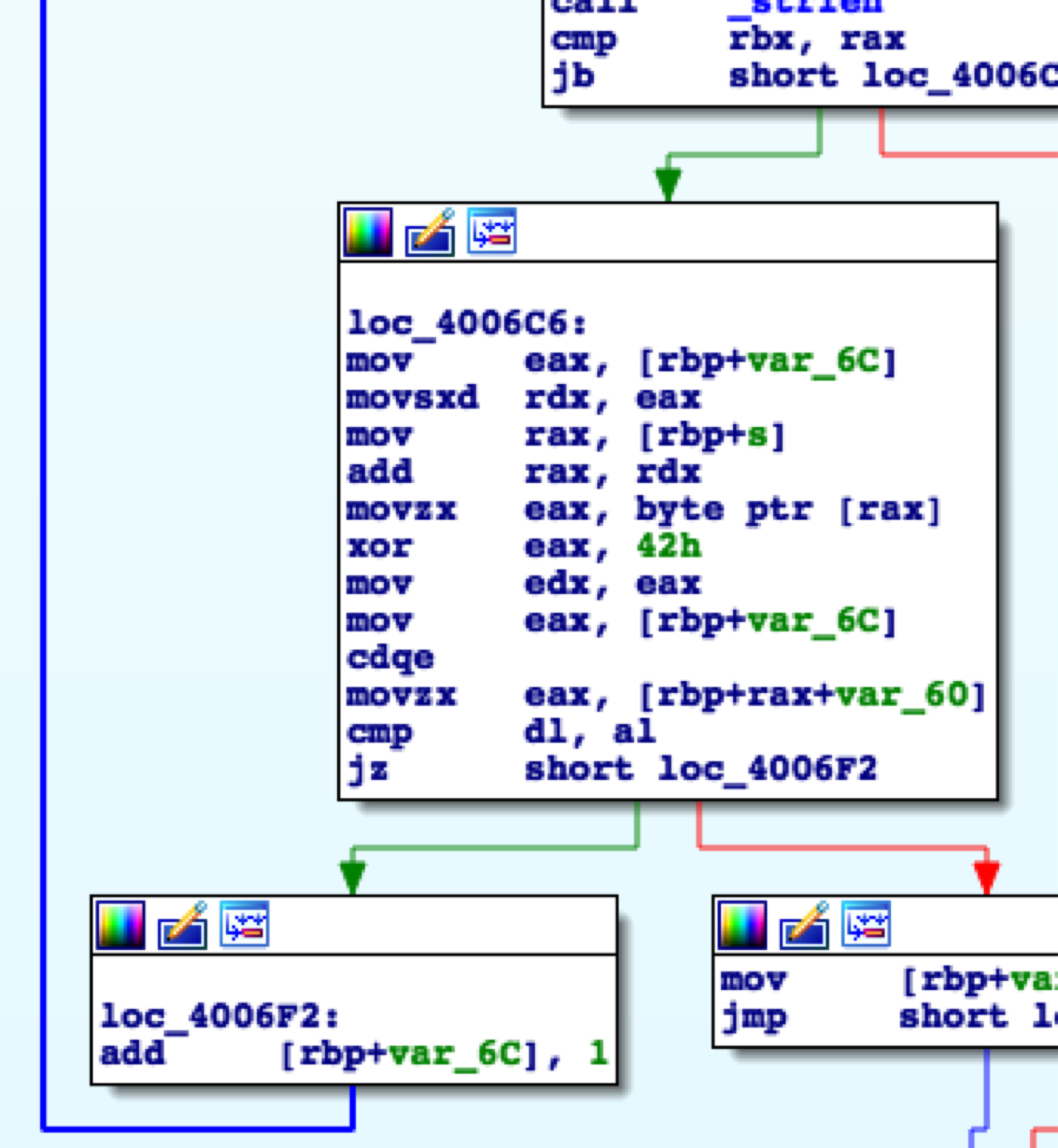

Opening the binary in IDA revealed a challenge quite similar to that of BabyRE0. In fact it was so similar that only one section of the binary really changed, specifically the section at loc_4006c6.

The important instruction to notice here is xor eax, 42h, what this does is take the byte in EAX and XOR is with the byte 42H. This kind of trick is known as a single byte XOR and is an extremely simple method of “encrypting” data. All you need to do to get the data back is XOR each byte in the flag string, which was setup in the first block of the binary, with the value 42H. This will reveal FLAG-{d0d383e0baa1543470c9bdd5f5ded71875d121f502bf494e21723250c9641c4b}. This is because the program loops over the string stored in memory and XORs each byte of that srting with the key.

BabyRE 2

We were given this unknown binary, can you find the flag?

- [ BabyRE2 ]

Is that the CRC32 checksum of a file?

Once again I ran Strings which revealed nothing. Like BabyRE 1 I jumped right into disassembling the binary without performing any debugging. IDA revealed some useful information right away. Looking at the functions on the left hand side we can see that the program imports some File IO functions as well as implementing its own CRC32 function. I decided to make some assumptions for sake of time, firstly I assumed the CRC32 function is a valid CRC32 implementation and secondly I assumed the file must be read by the program in some standard fashion so the flag isn’t located in the areas which are just reading the file but rather what happens after the file is read.

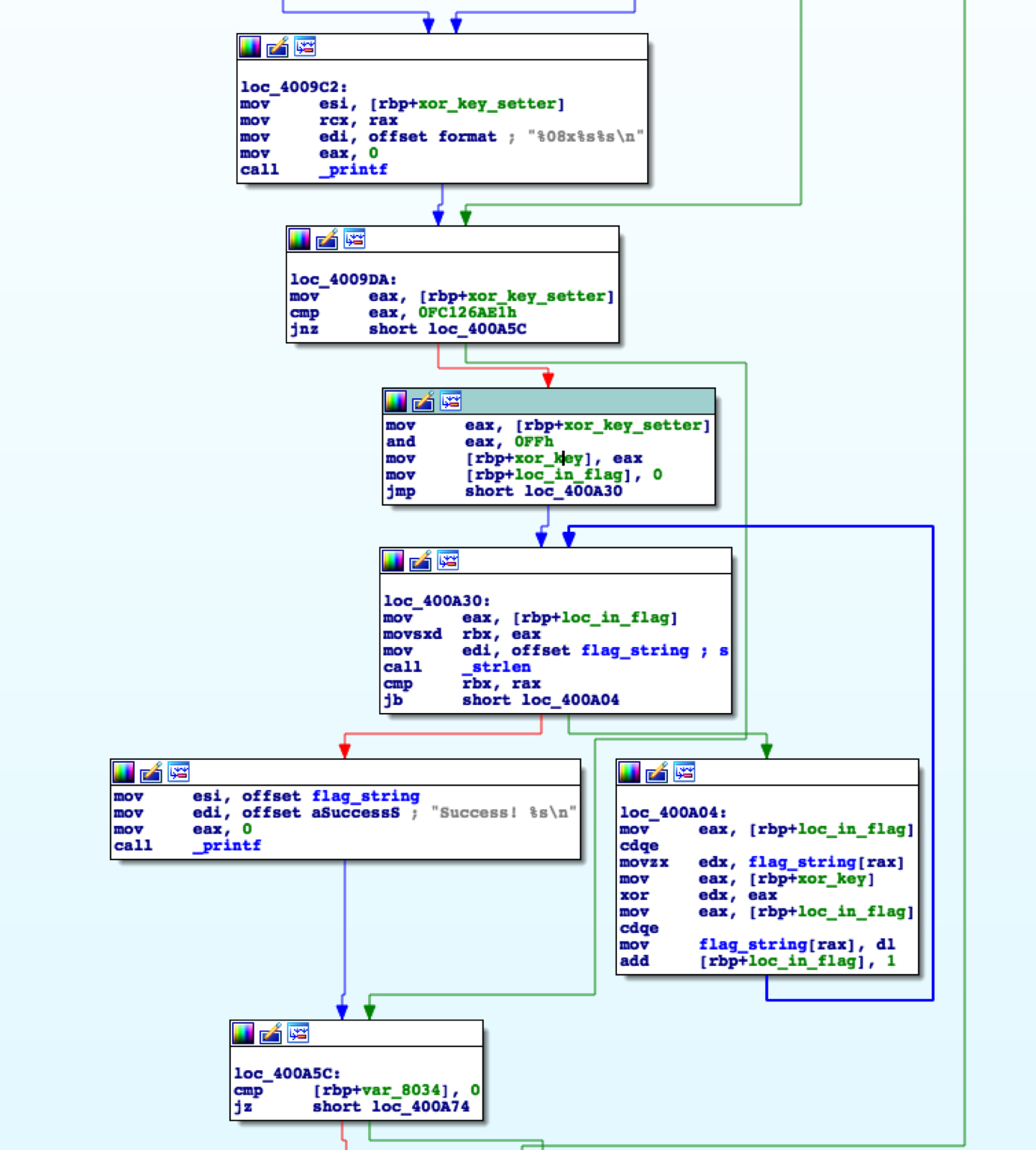

This was probably the largest binary I’ve had to analyze in a reversing challenge so far. I decided to approach it differently, instead of trying to understand the program from the top down, I tracked back from the success function. Much like the previous challenges the success case is reached when the length of the string has been read, however before that length is reached the function appears to loop over some memory denoted by flag_string and perform some operations. It should be noted that the flag_string is just stored as bytes in the data section at 0x601080 and can easily be read as hex.

1 | A7 AD A0 A6 CC 9A D1 D7 85 80 D6 D0 D7 D7 D1 D6 |

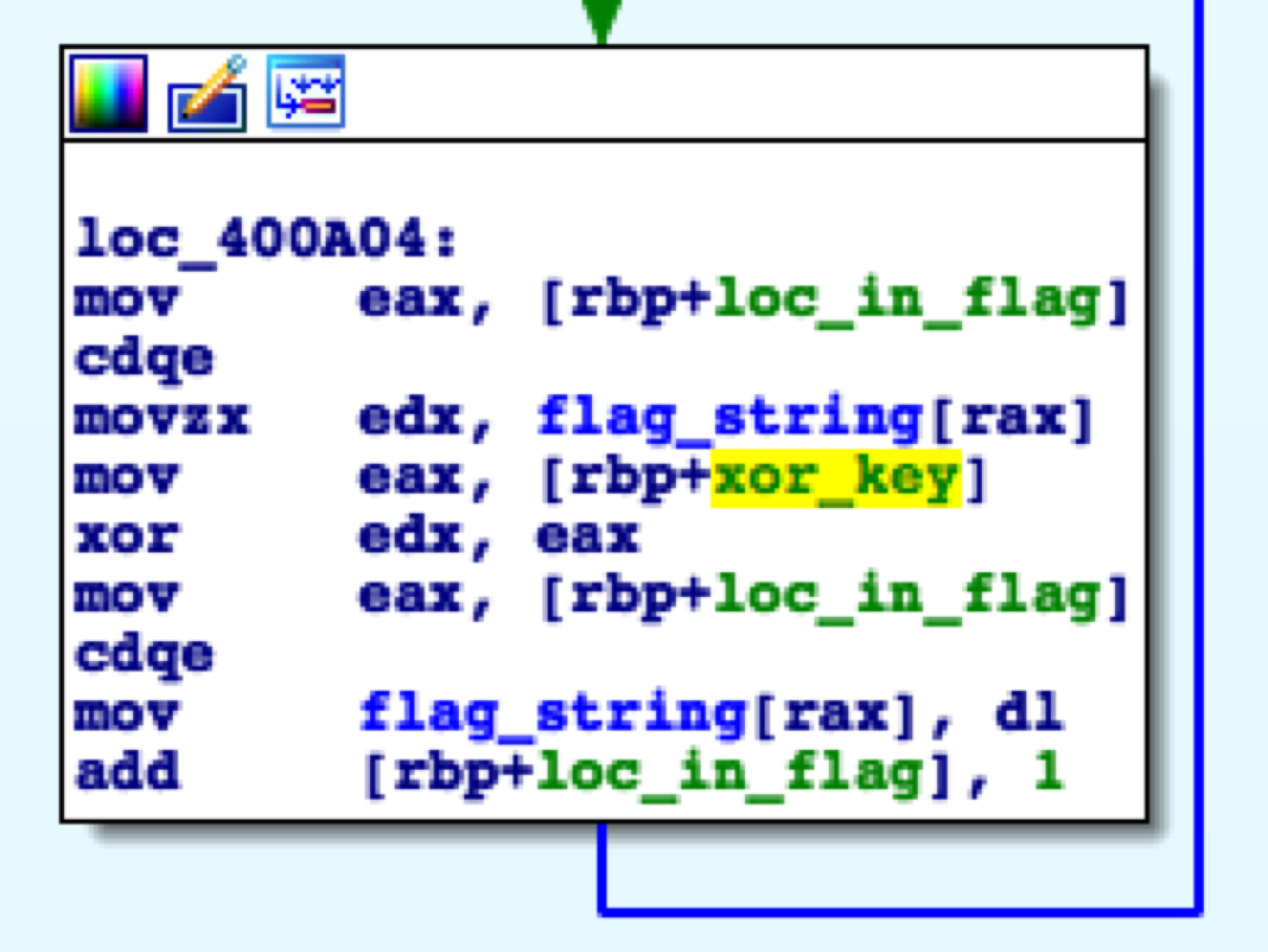

Taking a look at loc_400A04 we can see a similar setup to BabyRE 1, in which xor edx, eax is being used to decrypt the flag string. Looking closely at this block, the edx register is being used to read bytes from the flag string while the eax register is being used to store the key for the XOR operation. In the current block we can see that xor_key is moved into the eax register right before the xor operation, so lets investigate what could potentially be stored at that location in memory. In IDA this is easily done by clicking the variable, IDA will proceed to highlight all locations the var is used. Here’s an overview of the block that I just analyzed.

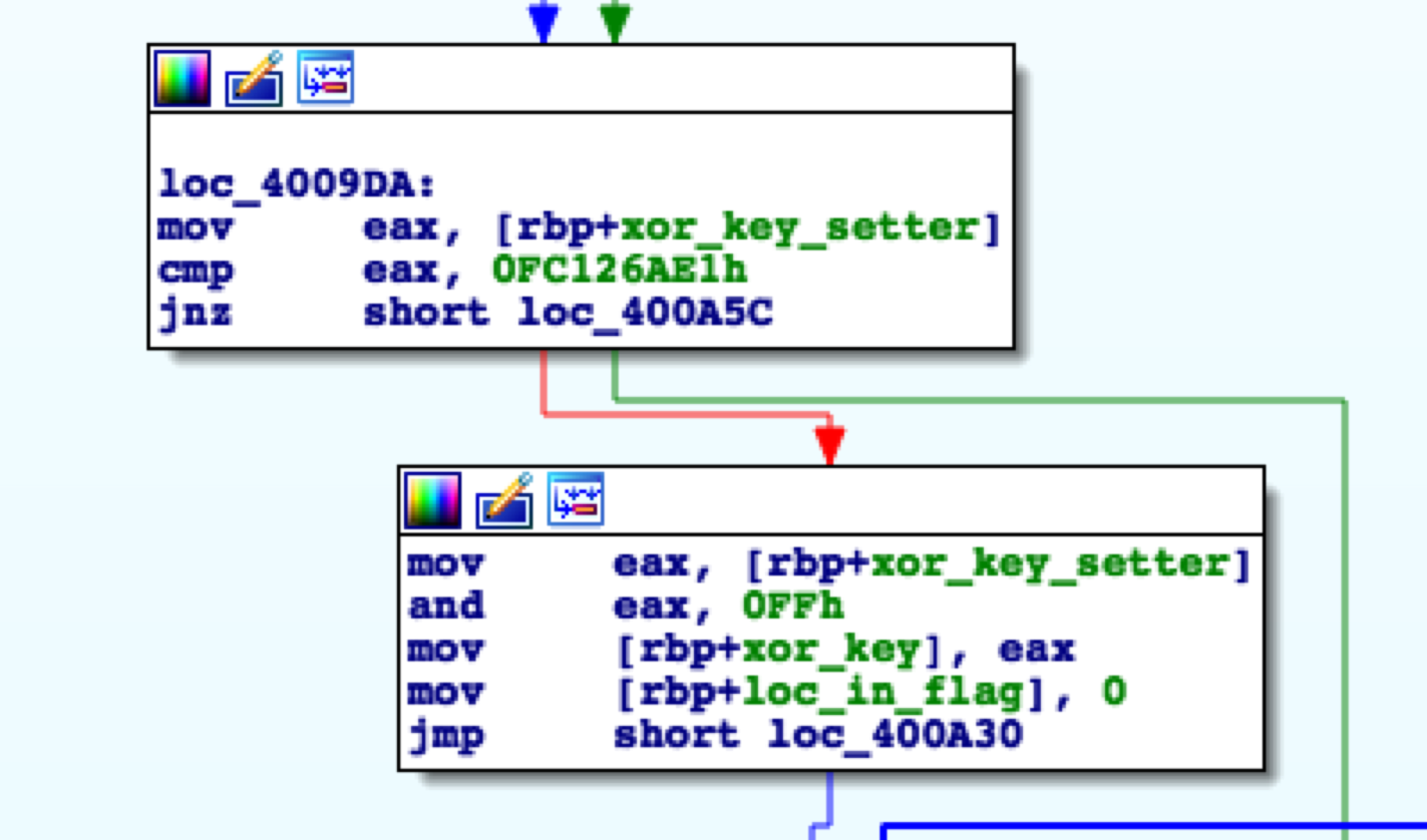

At this point what I did was follow all branches up to the first location where xor_key was used before the block which performed the xor operation. There’s a few things going on here which I’ll explain in a bit but essentially we can see that xor_key is set from eax, which is basically derived from xor_key_setter. It should be noted that ida will give variables a default name, for example var_8083, however you can rename them, much like I did here, and all the occurrences will be updated. So now we must see where xor_key_setter is set, tracing it back we notice the block right before uses xor_key_setter. I cheated a little bit here since I noticed a comparison being done after xor_key_setter was moved into eax, specifically the instruction is cmp eax, 0FC126AE1h. Great, a hardcoded value! With this we can determine that the desired value of xor_key_setter must be 0FC126AE1h. No need to trace back any further.

Now remember I said the xor key is basically derived from xor_key_setter. That’s because a small operation was performed to ensure that the key length is only one byte. Right now xor_key_setter is 4 bytes long and we need it to be one byte. To do this the program performs moves xor_key_setter into eax and then performs and eax, FF which effectively shortens the length of the key to one byte, thus making the XOR key E1.

Performing a single byte XOR on the flag string with E1 reveals FLAG-{06da71660714b7cf1406a056c76958cc5c5a06d22ce0b625dd076dd0988c9e43}

Personal ADs

There was a simple message board service where we could also store encrypted data using keys of any length. It had a few files already loaded into the system, though it only required 2 to solve. Knowing nothing about the encryption algorithm we were tasked to solve the challenge.

Here were the two files which it let us attempt to decrypt, if given the wrong key it would just print out what it attempted to decrypt. Perhaps these two files are related in some way? To solve you need know knowledge of the service, so feel free to have a go! (It might be slightly more challenging without being able to “test” posting encrypted messages, but its still doable)

The key for the flag is the same key being used for the bible file.

The encryption algorithm is just a multibyte XOR, can you find the key? It helps knowing that the first five bytes of the flag are FLAG{.

Going into this crypto challenge we know the first five bytes of the flag will always be FLAG{. Based on some simple testing, by creating my own strings and having the service encrypt/decrypt them, I was able to determine that a multibyte xor was being performed. With these two pieces of information it becomes possible to leak the first few bytes of the key string, we just needed to determine what they were. Before proceeding I dumped the contents of the flag and the bible file from the service by using the key “a” then just reversing the xor operation and storing the output in a file. This made manipulation much easier, especially since I could now use tools like CyberChef to modify the data.

Using CyberChef’s XOR bruteforce, with a 5 byte key & the first 5 bytes of the original flag string I was able to get the first 5 bytes of the key: otjge. With this information I attempted using that key on the bible file, and what do you know , the first five bytes of that file come out to: SCIEN. That appears to be English to me, implying that the bible and the flag possibly use the same xor key. The next step was to determine the length of the key. To do this I padded the key with a until it was possible to find other English words. I’d be curious to know if there’s a better approach to this since the whole process was quite manual. Anyhow I found the correct key length of 50 characters. All that was left was to find the correct values for each position, this can be done via bruteforce quite trivially. Basically just change the next character in the key until you find a place in the bible which seems to make more sense. For example when I first decrypted with otjgeaaaa... I saw the first word was SCIEN. That appears to be the word science, so all I did was change that first a until I found the right character revealing SCIENC and so on… Eventually it was revealed that the decryption key was otjgekximwdfdsbivpflrcifibjjprbsjqgpjtnkhbupanaggp. All that was left was to xor that with the flag file to reveal: FLAG-d4aa1015c97c5b31c3d5a6076613e931.

Space Time Forensics

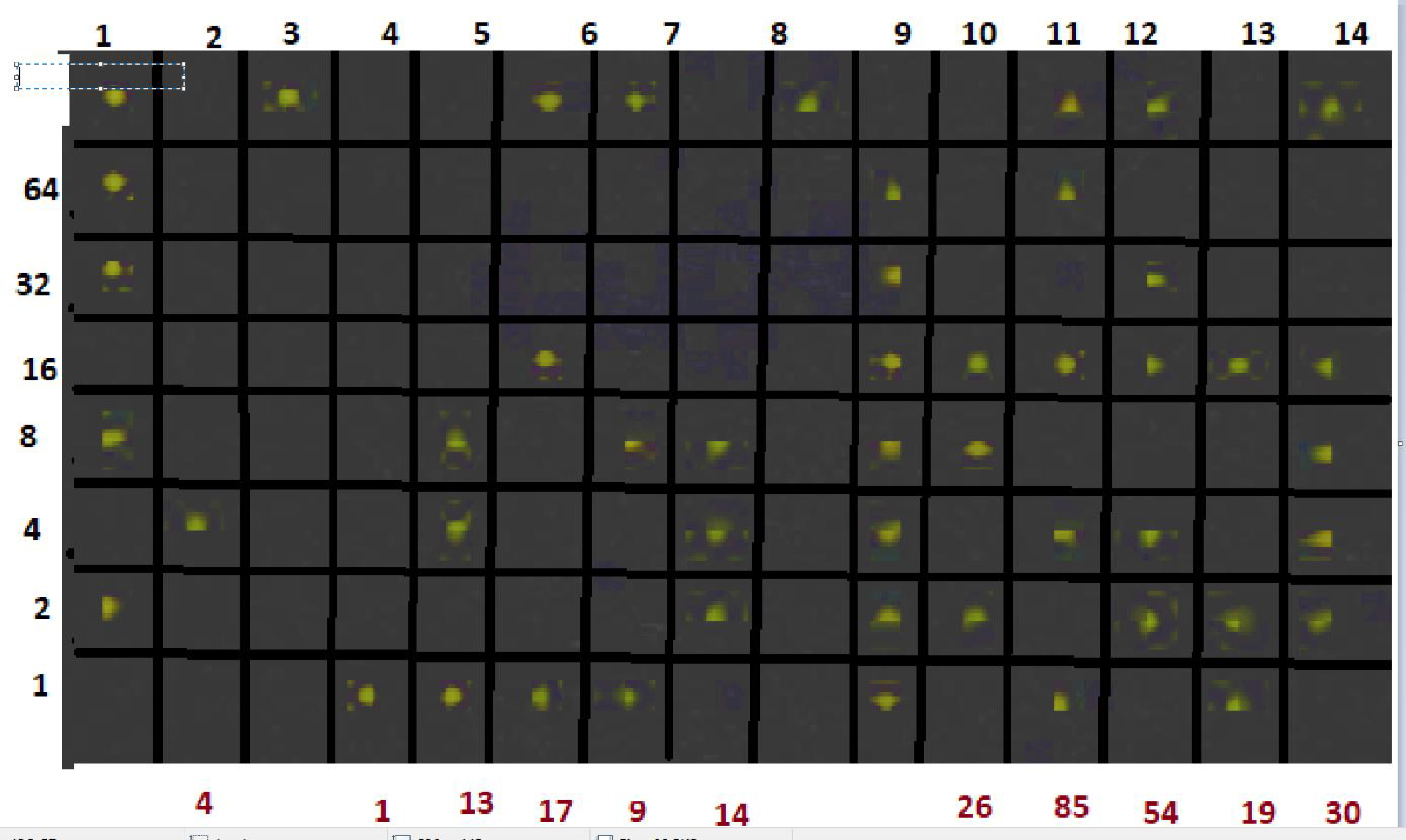

Here’s a scan of a piece of paper. Which model of printer was used to print that paper?

- [ Space ]

How did they know it was Snowden that leaked those documents?

This forensics problem is based around the fact that, for many years, colored printers printed near invisible information on every page they printed. It was some information encoded in yellow dots stating the print date and serial model. In 2005 the EEF was able to decode the information stored in these yellow dots. I remembered reading an article about them from around 2010 and through that was able to solve this challenge with ease. There were 3 stages to this challenge: the first part was the PDF which was given above, the second part was a physical piece of paper with the dots on it, and finally the 3rd part was a 2000 page book which was scanned but then one page was rescanned and you needed to find it.

Decoding the dots revealed the date which the piece of paper was printed: 20170914, thus that was the flag.

Secure Authentication

For this challenge we were given access to a website which had a form client side authentication. We were tasked with breaking the authentication:

Wast could make this easer?

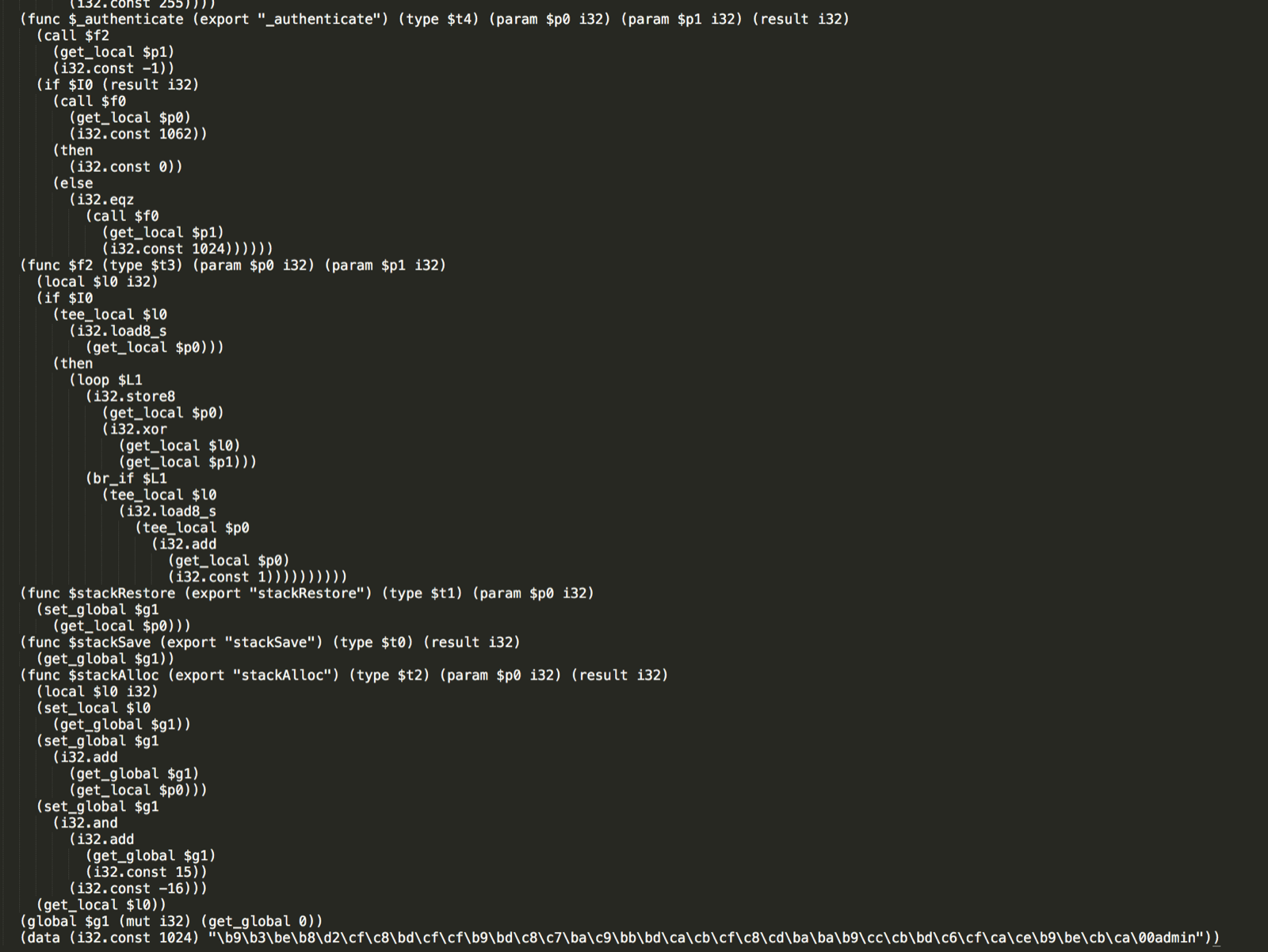

By analyzing the sources it was immediately evident that the application was using web assembly as the core for authentication. The JS in the main challenge page clearly called, or should I say ccalled, an authentication function with the username and password. Solving this challenge was going to rely on some reverse engineering knowledge. Once again I took the more difficult approach of disassembling instead of just debugging to understand what’s going on. I didn’t even realize it but chrome and firefox actually both support debugging of web assembly!I opted to use wabt’s online disassembler to convert the binary to WebAssembly Text Format, or wat for short. With this I was able to begin disassembly and commenting.

Since I’m not familiar with WebAssembly and much less so with disassembling it I decided to start with inspecting the entire WAT file to look for some clues. At the second highest level we can see a few things: some type decelerations, a few imported functions, some function decelerations (f0, f2, authenticate, and some stack manipulations), a couple of global vars, and a data section. Two things stood out here:

The data section

Here we can see a bunch of data followed by the word admin. The data appears to be hex, denoted by \XX. We also know from earlier some “ccall” was used and the data ends in \00. That looks like a null byte! So what it seems like is that we have some binary data, likely the encrypted password, followed by the username admin.

The Authenticate function

Before diving into the function itself I needed to do some research on WebAssembly and what the instructions and types are. For the most part everything in this challenge is pretty self explanatory however I wanted to make sure I was reversing it correctly. The Mozilla documntation is quite thorough on WASM and I would really suggest checking it out.

Earlier we saw that the javascript made a call to the authenticate function passing the username and password as parameters. We can see that they are then stored in local vars on the stack as $p0 and $p1 respectively. Right away the first instruction we see being executed is a call to f2 passing the $p1 var (password) as well as -1 constant value. This is probably a good area to investigate since it is using the password variable. note the following may be wrong but it was how I solved it at the time, if you know WASM please correct me! From a very high level this function sets up a local variable, $l0, as a 32 bit integer and then loads the $p1 local var into $l0. However, during this process the load8_s instruction is used which, from my understanding, loads the signed byte into the local var. Remember that the the constant passed was -1, so in binary that would be ff, thus making the variable $l0 become ffffffff. Finally we loop over $L1… not too sure where $L1 came from but I just assumed it was a local counter related to the length of the global data… doesn’t really matter too much in the context of this problem though if anyone knows where $L1comes from please let me know! Anyhow, in the loop we can see that an XOR is performed with the value being stored back into $p0.

So that was probably a lot to take in, but the gist of it is that we loop over the password and XOR it with a constant of ff in the function $f2, thus all that is happening in the WASM is a single byte xor on the password. From this point forward I made the assumption that the bytes stored in global memory were XORed with the value ff and revering this process reveals: FLAG-07B00FB78E6DB54072EEF34B9051FA45. Success!

Hopefully you all learned something new too! See ya next year NSec!